THE MEANING OF MONASTIC ROBES

by Ven. Geshe Lhundrub Sopa( reprinted from Special Edition of MANDALA Magazine )

( reprinted from Special Edition of MANDALA Magazine )

|

The dhonka has much historical significance. It was created in the time of Tsong Khapa, in the 14th century; before then, monks dressed in the Indian Hinayana style, with nothing much on the upper part of the body. Tibet is very cold, though, so they created this upper garment. It is made of maroon and yellow cloth, sometimes all maroon. The two shoulders represent the lion's mane. The lion is the king of beasts who has no fear of other beings, remaining relaxed and peaceful. The same with anyone following Vinaya: they do not need to fear being born in suffering rebirths; they are on the path of emancipation. |

|

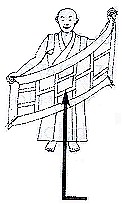

| The shemdap is made of patches and is maroon. Originally, you would cut up the cloth into different pieces and then sew it together; now we simply sew it so it looks patched. As His Holiness said once, "It's not of good quality, and it's patched. If it was of good material and in one piece, your could sell it and gain something. This way you can't. This reinforces our philosophy of becoming detached from worldly goods." |  |

| The folds in the robes (at least in the Gelug lineage) have particular significance. The fold on the right side turn towards the back, which symbolizes that the monk or nun has left behind worldly concerns and activities, as well as following negative actions. The folds on the left turn towards the front, symbolic of following the Buddhist path and virtuous activities--the purpose is to go towards that. Monastics should always remember this when they put on their robes. |  |

| The chögu is yellow and is usually worn during confession ceremony and teachings. It is similar to the Hinayana robe. It is also made of many pieces. |  |

| For day-to-day life, monks and nuns don't wear the chögu; they wear the zen, which is maroon, the same as the shemdap. |  |

| The dingwa is made of wool and is put on top of your cushion. Monks and nuns are supposed to always take it with them. Nowadays it's not used much, only for teachings and ceremonies. If you visit someone, you would sit on it so that it protects the person's seat from damage: if you spill something, for example, it's your own cloth that gets damaged. |  |

| The hat is worn during special ceremonies. The bottom part is yellow and has the handle in the back with two handles. Inside is white, symbolic of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion; the handle inside is blue, symbolic of Vajrapani, the Buddha of Power; and the handle outside is reddish orange and symbolizes Manjushri, the Buddha of Wisdom. The many threads standing upright represent the thousand Buddhas of this age on top of your head. The yellow represents the purity of the teachings, similar to how gold is considered pure and free of stains. |  |