The Diamond-Cutter Sutra

Course 6

by Geshe Michael Roach

The Diamond-Cutter Sutra

Level 1 of Middle-Way Philosophy (Madhyamika).

The Diamond-Cutter Sutra

The Diamond-Cutter Sutra

Level 1 of Middle-Way Philosophy (Madhyamika).

Sungbum by Author (English): SP0024

www.asianclassics.org/download/SungEng.html

SP0024: “The Sun that Illuminates the Profound Meaning

of the Excellent Path for Travelling to Freedom”

a commentary on The Diamond-Cutter Sutra

www.world-view.org/download/texts/sungbum/rtf/SP0024M.RTF

ACIP has recently been able to obtain what to our knowledge is the only native

Tibetan commentary on The Diamond-Cutter Sutra, which has played such a key role

in Asian philosophical life that the Chinese translation, dated to 868 AD,

is the oldest complete printed book known in the world.

The present commentary was composed by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup

(Co-ne bla-ma Grags-pa bshad-sgrub), who is the author of an alternate series

of textbooks for Sera Mey University. Chone is a famous monastic university

in the Amdo region of eastern Tibet, and this is where representatives

of Sera Mey were able to make a photocopy of the master's entire collected works,

after over 30 years and many attempts to do so!

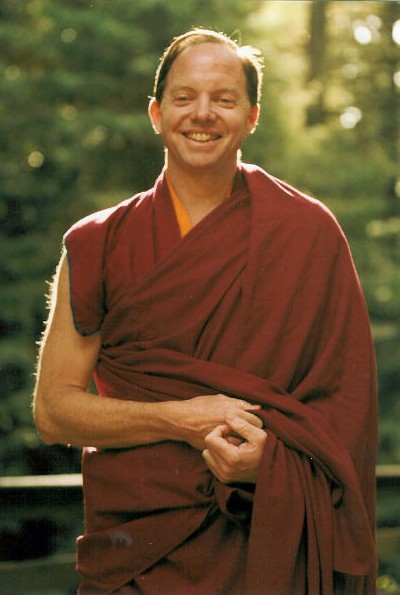

The author, Geshe Michael Roach, 7th of March 2000

"I'm going into a silent three-year Buddhist retreat today...

Amazon.com has been good enough to encourage me to write a few "words from the author" for two new books that have come out recently through the kind efforts of my editors at Doubleday/Random House. I'm going into a silent three-year Buddhist retreat in the Arizona desert today, a lifetime dream, and so really this is my last chance to write something. One of the books is called "The Diamond-Cutter: the Buddha on Strategies for Managing Your Business and Your Life." It reflects lessons I learned from over 20 years of intense studies in Tibetan monasteries, and 16 years of intense corporate life in a very large and crazy diamond corporation in New York: how we used the great ideas of the ancient wisdom of Tibet to get to sales of over $100 million a year, and had a fun and meaningful time doing it. All I have to say about this book is this. Think about the great discoveries of our time. A lot of older Tibetans that I know, for example, are in constant awe that we learned how to make iron boxes fly in the sky and carry people around. And we figured out how to get little wafers of sand to connect the world into a vast web community and market. And unfortunately we learned how to destroy whole cities by smacking a few little particles together the right way. The Tibetans have, quite frankly, made a few discoveries about the way things work that are just as earth-shattering, and just as hard for us, from our very different cultural background, to learn and appreciate. Simply put, they have made discoveries about the actual fabric of reality, about how things work, very precisely how to get the things you want to happen to happen, that are just as amazing as flying iron boxes. The book teaches you how to use these discoveries to succeed in your business, family, and also your emotional life. When you really think about it, figuring out why things happen to us, and how to change them, has been the goal of humankind for as long as we've been around. The book teaches you how, exactly. And that's no exaggeration. We used this stuff in a very real way to bring our sales up over that $100 million mark, no joke, and then we used the money to help people in a real way. And by the way, all the royalties of both books are going 100% to help Tibetan refugees. So check it out. Hey, would someone who's going to be silent for three years after today be pulling your leg? The second book is called "The Garden." For this book I took the challenge of taking all the beautiful ideas I ever learned in those incredible Tibetan monasteries, and putting them down in what I hoped would be a classic little tale, something like the "Little Prince," something that people of all ages and from all walks of life could read say on a plane, and by the time they get to where they're going they've had a very powerful, accurate, and digestible dose of the greatest ideas of the other half of humanity: the ancient wisdom of Tibet, China, India, Japan, Mongolia. I wanted it to be something timeless, and something that people could really use in their own lives, and the lives of their families and children, to make our world a better and happier place. I really hope you get a chance to read it, and spread it around, it's short and fun to read and makes a great, meaningful gift. Last last thing: the old tradition of Tibet says that, when someone does their three-year silent retreat, it always goes a lot better if other people are sending them good thoughts. So as you read the two books, as I hope you will, then sometimes look up and think about the small group of us here in the desert,

The author, Geshe Michael Roach, 7th of March 2000

"I'm going into a silent three-year Buddhist retreat today...

Amazon.com has been good enough to encourage me to write a few "words from the author" for two new books that have come out recently through the kind efforts of my editors at Doubleday/Random House. I'm going into a silent three-year Buddhist retreat in the Arizona desert today, a lifetime dream, and so really this is my last chance to write something. One of the books is called "The Diamond-Cutter: the Buddha on Strategies for Managing Your Business and Your Life." It reflects lessons I learned from over 20 years of intense studies in Tibetan monasteries, and 16 years of intense corporate life in a very large and crazy diamond corporation in New York: how we used the great ideas of the ancient wisdom of Tibet to get to sales of over $100 million a year, and had a fun and meaningful time doing it. All I have to say about this book is this. Think about the great discoveries of our time. A lot of older Tibetans that I know, for example, are in constant awe that we learned how to make iron boxes fly in the sky and carry people around. And we figured out how to get little wafers of sand to connect the world into a vast web community and market. And unfortunately we learned how to destroy whole cities by smacking a few little particles together the right way. The Tibetans have, quite frankly, made a few discoveries about the way things work that are just as earth-shattering, and just as hard for us, from our very different cultural background, to learn and appreciate. Simply put, they have made discoveries about the actual fabric of reality, about how things work, very precisely how to get the things you want to happen to happen, that are just as amazing as flying iron boxes. The book teaches you how to use these discoveries to succeed in your business, family, and also your emotional life. When you really think about it, figuring out why things happen to us, and how to change them, has been the goal of humankind for as long as we've been around. The book teaches you how, exactly. And that's no exaggeration. We used this stuff in a very real way to bring our sales up over that $100 million mark, no joke, and then we used the money to help people in a real way. And by the way, all the royalties of both books are going 100% to help Tibetan refugees. So check it out. Hey, would someone who's going to be silent for three years after today be pulling your leg? The second book is called "The Garden." For this book I took the challenge of taking all the beautiful ideas I ever learned in those incredible Tibetan monasteries, and putting them down in what I hoped would be a classic little tale, something like the "Little Prince," something that people of all ages and from all walks of life could read say on a plane, and by the time they get to where they're going they've had a very powerful, accurate, and digestible dose of the greatest ideas of the other half of humanity: the ancient wisdom of Tibet, China, India, Japan, Mongolia. I wanted it to be something timeless, and something that people could really use in their own lives, and the lives of their families and children, to make our world a better and happier place. I really hope you get a chance to read it, and spread it around, it's short and fun to read and makes a great, meaningful gift. Last last thing: the old tradition of Tibet says that, when someone does their three-year silent retreat, it always goes a lot better if other people are sending them good thoughts. So as you read the two books, as I hope you will, then sometimes look up and think about the small group of us here in the desert,

trying really hard to figure out what Buddha and Jesus did

when they went on similar trips to the wilderness. It'll help a lot.

Thanks, and see you later! " --

Geshe Michael Roach

trying really hard to figure out what Buddha and Jesus did

when they went on similar trips to the wilderness. It'll help a lot.

Thanks, and see you later! " --

Geshe Michael Roach

The Diamond-Cutter Sutra (Vajracchedikasutra) is a brief but important work on the subject of the Prajna Paramita, the Perfection of Wisdom, which refers to a combination of compassion and the understanding that nothing occurs outside of ethical cause and effect. This text was selected because ACIP has recently been able to obtain what to our knowledge is the only native Tibetan commentary to this work, which has played such a key role in Asian philosophical life that the Chinese translation, dated to 868 AD, is the oldest complete printed book known in the world.

The Diamond-Cutter Sutra (Vajracchedikasutra) is a brief but important work on the subject of the Prajna Paramita, the Perfection of Wisdom, which refers to a combination of compassion and the understanding that nothing occurs outside of ethical cause and effect. This text was selected because ACIP has recently been able to obtain what to our knowledge is the only native Tibetan commentary to this work, which has played such a key role in Asian philosophical life that the Chinese translation, dated to 868 AD, is the oldest complete printed book known in the world.

There are two existing Tibetan translations of early Sanskrit commentaries on the work; these are contained in the Tengyur collection of philosophical commentaries and will be input by ACIP in the near future. The edition used for the Diamond-Cutter itself was the very clear 1730 carving from Derge, Tibet. A second version has also already been input; it is in the dpe-thung format and is probably fairly recent in publication; although the colophon mentions no date of publication, it does mention the sponsor as one Palden Tsultrim (dPal-ldan tsul-khrims).

The present commentary was composed by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (Co-ne bla-ma Grags-pa bshad-sgrub), who is the author of an alternate series of textbooks for Sera Mey University. Chone is a famous monastic university in the Amdo region of eastern Tibet, and this is where representatives of Sera Mey were able to make a photocopy of the master's entire collected works, after over 30 years and many attempts to do so. Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup's dates are 1675-1748.

Most students are likely to find Master Shedrup's commentary easier to follow than either of the early Indian commentaries. It adheres closely to the root text and explains in plain language the point being made in each of the many cryptic lines of the original. In a number of places, Master Shedrup gives very helpful glosses of specific terminology of the Sanskrit, such as his treatment of the Tibetan translation sems-can.

The original woodcarving for the commentary was unusually corrupt, a problem complicated by the fact that for input we had only a photocopy of an often blotchy xylograph print. Fortunately ACIP was able to take advantage of the availability of several highly qualified native scholars to reconstruct unclear readings in a great number of cases. Hopefully conditions in occupied Tibet will one day improve to where a better original can be consulted.

It is interesting to note that the word "diamond" occurs nowhere in the Diamond-Cutter Sutra except for the title. And yet the title itself contains perhaps the most profound message of Asian philosophy, which is fitting for the oldest book in the world. Diamond is the closest thing to an absolute in the natural world: nothing in the universe is harder than diamond; nothing can scratch a diamond. Diamond is absolutely clear: if a diamond wall were built around us we would not be able to see it, even if it were many feet thick. In these senses diamond is close to what Buddhist philosophy terms "absolute truth," or emptiness, which is described below in the hypertext essay, The Marriage of Ethics and Emptiness.

Absolute truth is first perceived directly in a deep state of concentration; the state of mind at this point is called the "path of seeing." Subsequent to seeing absolute truth directly, we understand that reality as we normally experience it, though valid, is something less than absolute. All objects possess a quality of absolute truth, or emptiness: all objects are void of any self-nature which does not depend on our projections. In this sense we are surrounded by absolute truth, but have never been able to see it: it is as if this level of reality were like a wall of clear diamond.

The diamond is close to ultimate reality, but it is not ultimate. In this sense it can be "cut": it can serve only to remind us of the real ultimate. And so it is important to refer to the work with its full name, the Diamond-Cutter.

The ACIP disk catalog numbers are KD0016 for the Diamond-Cutter and S0024 for Master Shedrup's commentary.

The following selections are taken from "Sunlight on the Path to

Freedom", written by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of Sera Mey Tibetan

Monastery. The original root text of the sutra by Lord Buddha is included in darker type. Herein contained is a commentary upon The Diamond Cutter Sutra

entitled Sunlight to See the Profound, the Excellent Path to Travel to Freedom. I bow down to Manjughosha. I bow down to the Lord of the Able Ones, the king of sponge-like clouds Floating high in the great expanse of the sky, the dharma body, unobscured, Stunning in the glory of his thunder, the sound of emptiness profound, Sending down to fields of students a stream of rain both of the goals. I prostrate myself at the feet of Subhuti, a realized being who is The Wheel of Solid Earth, a destroyer of the enemy in disguise, Masterful in posing the questions and replies of the profound, Prophesied to be the supreme of those who've finished all affliction. I make obeisance to the spiritual friends who one by one appeared To clarify the deepest teaching, as foretold by the Victors: Nagarjuna, and Aryadeva, and Chandrakirti too, Lobsang the Victor come again father and sons and the rest. Here I will, with great feelings of faith and in keeping with my own

capacity, offer a commentary in explanation of the Perfection of Wisdom in 300 Verses,

more commonly known as the Diamond Cutter. It would seem that this text is rather

difficult to comment upon correctly, for a number of reasons. First of all, the work is

largely devoted to elucidating the meaning of the absence of a self-nature. Moreover, Lord

Buddha repeats himself quite a number of times during the teaching. Finally, there appears

to be but a single explanation of the work by the masters of ancient India, and none by a

Tibetan at all. Nonetheless, I will undertake a commentary, to the best of my intellectual

ability. We will proceed in three steps: the preliminaries, the actual body of

the text, and the conclusion. The first part here has three sections of its own: a

translation of the title, along with an explanation of its significance; the translator's

obeisance; and setting the scene. Here is the first. In the language of India, this teaching is called the Arya Vajra

Chedaka Nama Prajnya Paramita Mahayana Sutra. In the language of Tibet, it is called

the Pakpa Sherab Kyi Paroltu Chinpa Dorje Chupa Shejawa Tekpa Chenpoy Do. [In the

English language, it is called An Exalted Sutra of the Greater Way on the Perfection of

Wisdom, entitled "The Diamond Cutter."] The root text here begins with "In the language of India, this

text is called the Arya Vajra..." The Tibetan equivalents of the words in the

title are as follows. Arya means pakpa, [or "exalted."] Vajra

means dorje, [or "diamond."] Chedaka is chupa, [or "cutter."]

Prajnya is sherab, [or "wisdom."] Para is paroltu,

[or "to the other side,"] while ita means chinpa, [or

"gone," and the two together mean "perfection."] Nama is for shejawa, [which means "entitled."] Maha

stands for chenpo, [or "greater."] Yana means tekpa,

[which is "way," or "vehicle."] Sutra translates as do,

[or "sutra," meaning the teaching of an enlightened being.] How do we get this word paramita? The ending am is

required between the words para and ita, to represent the second grammar

case. In combination the a of the am drops out, and the resulting m

is attached to the ita, which gives us mita. Here is the significance of the name. The worldly god named Hundred

Gifts, or Indra, wields a diamond bolt, which no physical object in the entire world can

destroy. A mere touch of this bolt though can reduce mountains of stone and other such

entities to piles of dust. The subject of this work is the actual perfection of wisdom;

that is, the wisdom with which one perceives emptiness. The point of the title is that the

antithesis of this wisdom can never affect it in the least; and that the wisdom, on the

other hand, cuts from the root everything involved with the mental afflictions, and each

and every suffering. I bow down to all Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The import of the second point, the translator's obeisance, is

self-evident. These words once I heard. The Conqueror was residing at Shravasti, in

the park of Anatapindada at the gardens of Prince Jetavan. In convocation with him were a

great gathering of 1,250 monks who were listeners, as well as an immense number of

bodhisattvas who were great beings. Third is the third preliminary, where the scene is set. The speaker is

the person who compiled the words of this text, who says "I heard"

the following. Once, meaning at a certain time, the Conqueror was residing at

Shravasti, in the park of Anatapindada at the gardens of Prince Jetavan. In convocation

with him that is, together with him were a great gathering of 1,250 monks who were

listeners, as well as an immense number of bodhisattvas who were great beings. In India there were six great cities, including the one known as

"Shravasti." This particular city was located in the domain of King Prasenajita,

and contained a particularly excellent site the exquisite gardens of one known as Prince

Jetavan. There came a time, several years after the Conqueror attained his

enlightenment, when a certain householder by the name of Anatapindada resolved that he

would construct a large, wondrous temple where Lord Buddha and his retinue could reside on

a regular basis. To this end he approached Prince Jetavan and purchased his gardens by

paying him many thousands of gold coins, enough in fact to fill the gardens themselves. Jetavan as well offered to the Conqueror a parcel of land that had been

part of the quarters for the caretakers of the property. In these gardens Anatapindada,

availing himself of the abilities of Shariputra, directed artisans from the lands of both

gods and men to construct an extraordinary park. When the park was completed, the Conqueror, perceiving that Jetavan

wished it, named the main temple after him. Anatapindada, by the way, was a great being

who had purposely taken a birth as someone who could act as the Teacher's sponsor. He had

the power to see deposits of precious gems and metals deep under water or below the earth

itself, and could utilize these riches whenever he wished. In the morning then the Conqueror donned his monk's robes and outer

shawl, took up his sage's bowl, and entered the great city of Shravasti for requesting his

meal. When he had collected the food, he returned from the city and then partook of it.

When he had finished eating he put away his bowl and shawl, for he was a person who had

given up the later meal. He washed his feet and then seated himself on a cushion that had

been set forth for him. He crossed his legs in the full lotus position, straightened his

back, and placed his thoughts into a state of contemplation. In the morning then the Conqueror all for the sake of his disciples

donned the three parts of a monk's attire, took up his sage's bowl, and went

to the great city of Shravasti for requesting, in order to request, his meal.

He accepted his food and then, after coming back, partook of it. When he had finished eating he put away his bowl and so on, for

he was a person who had given up the later meal; that is, who would never go to

request a meal in the latter part of the day. He washed his feet, bathed them, and

then seated himself on a cushion that had been set forth for him. He crossed his legs in

the full lotus position, and straightened his back. Then he placed his

thoughts into a state of contemplation, knowing that he was about to deliver this

teaching. We should speak a bit here about the fact that the Conqueror went to

request food. As far as the Buddha is concerned, there is no need at all to go and ask for

his meal. Rather, he does so only so that his disciples will have an opportunity to

collect masses of good karma, or else in order to give instruction in the Dharma, or for

some similar reason. The Sutra of Golden Light explains how it is completely

impossible for a Buddha to suffer hunger or thirst. And even if they did need to eat or

drink something, it is a complete impossibility that the Buddhas would ever find

themselves without sufficient supplies; they could take care of themselves perfectly well,

for they have gained total mastery over what we call the "knowledge of the store of

space." They have as well the ability, should they so desire, to turn dirt or stones

or other things of the like into gold, or silver, or precious jewels. Furthermore they have the power to transform such objects, and also

inferior kinds of food, into feasts of a thousand delectable tastes. No matter how poor

some meal might be, it turns to a matchless, savory banquet as soon as a Buddha touches it

to his lips delicious in a way that no other kind of being could ever in his life

experience. The Ornament of Realizations is making this same point when it says

"To him, even a terrible taste turns delicious to the supreme." There was a time before when, for three months, the Teacher pretended

to be so destitute that he was forced to eat the barley that we usually use for horse

fodder. His disciple Ananda was depressed by the sight, thinking to himself, "Now the

day has come that the Teacher, who was born into royalty, is reduced to eating horse

fodder." The Teacher then took a single piece of the grain from his mouth, handed it

to Ananda, and instructed him to eat it. The disciple complied, and was filled; in fact,

for an entire week thereafter he felt no urge to eat anything at all, and was overcome

with amazement. This incident applies here too. The Golden Light relates how despite the fact that the Teacher

appeared to have to go for requesting his meal and seemed as well to eat it, in truth he

did not eat, and had no feces or urine either. The Sutra of the Inconceivable

explains as well that the holy body of the Ones Thus Gone are like a lump of solid gold:

there is no cavity inside, and no organs like the stomach, nor large or small intestines.

This is actually the way it is. And then a great number of monks advanced towards the Conqueror and,

when they had reached his side, bowed and touched their heads to his feet. They circled

him in respect three times, and then seated themselves to one way. At this point the

junior monk Subhuti was with the same group of disciples, and took his seat with them. The root text is saying that, then, a great number of monks too advanced

to the side of (which is to say approached) the Conqueror. Then they circled

him in respect three times, and seated themselves to "one way"; that is,

they sat down all together. Not only that, but at this point the respected elder

named Subhuti was with this same group of disciples, and took his seat with them. We now begin the second step in our commentary to the sutra, which is

an explanation of the actual body of the text. This itself comes in two parts: a

description of how the teaching was initially requested, and then an explanation of the

series of answers that followed. Here is the first of these. And then the junior monk Subhuti rose from his cushion, and dropped the

corner of his higher robe from one shoulder in a gesture of respect, and knelt with his

right knee to the ground. He faced the Conqueror, joined his palms at his heart, and

bowed. Then he beseeched the Conqueror in the following words: The root text next describes how the junior monk Subhuti then rose

from the cushion where he had been seated, and dropped the corner of his

"higher" robe meaning his upper robe from his left shoulder in a

gesture of respect. He placed the sole of his left foot on the ground, and then

knelt with his right knee as well. He faced in the direction of the

Conqueror, joined his palms at his heart, and bowed. Then he beseeched the Conqueror in

the following words. Oh Conqueror, the Buddha the One Gone

Thus, the Destroyer of the Enemy, the Totally Enlightened One has given much beneficial

instruction to the bodhisattvas who are great beings. Whatever instruction he has ever

given has been of benefit. And the One Gone Thus, the Destroyer of the Enemy, the Totally

Enlightened One, has as well instructed these bodhisattvas who are great beings by

granting them clear direction. Whatever clear direction he has granted, oh Conqueror, has

been a wondrous thing. Oh Conqueror, it is a wondrous thing. To put it simply, Subhuti beseeches the Buddha by saying: Oh Conqueror, you have given much instruction to the

bodhisattvas who are great beings; and in a spiritual sense it has been of the highest

benefit, the ultimate help, for both their present and future lives. Whatever

instruction you have ever given, all of it has been of this same benefit. You have as well instructed these bodhisattvas by granting them

three kinds of clear direction. You have directed them towards the source, and

towards the dharma, and towards the commands. Subhuti then tells the Conqueror how wondrous this is, and so

on. In Master Kamalashila's thinking here the word "source" would

refer to directing a disciple to a spiritual guide. The word "dharma" would

signify how this guide leads his disciple to engage in what is beneficial. And the

"commands" would describe the Buddha's directions: "You, my bodhisattva,

must act to help all living beings." Oh Conqueror, what of those who have entered

well into the way of the bodhisattva? How shall they live? How shall they practice? How

should they keep their thoughts? This did Subhuti ask, and then... This brings us to the actual way in which the sutra was requested.

Subhuti asks the Conqueror, "What of those who have entered well into the way of

the bodhisattva?" He phrases his question in three different sections: "How

shall they live? How shall they practice? How should they keep their thoughts?" Here secondly we explain the Buddha's reply. ...the Conqueror bespoke the following words, in reply to Subhuti's

question: Oh Subhuti, it is good, it is good. Oh Subhuti, thus it is, and thus is

it: the One Thus Gone has indeed done benefit to the bodhisattvas who are great beings, by

granting them beneficial instruction. The One Thus Gone has indeed given clear direction

to the bodhisattvas who are great beings, by granting them the clearest of instruction. The Conqueror is greatly pleased by the request that Subhuti

submits to him, and so he says "It is good." Then he provides his

affirmation of the truth of what Subhuti has spoken, by assenting that the One Thus

Gone has indeed done benefit to the bodhisattvas who are great beings, and has indeed

given them clear direction. And since it is so, oh Subhuti, listen now to

what I speak, and be sure that it stays firmly in your heart, for I shall reveal to you

how it is that those who have entered well into the way of the bodhisattva should live,

and how they should practice, and how they should keep their thoughts. "And since this reason is so," continues the

Buddha, "listen well now to what I speak, and be sure that it stays

firmly, without ever being forgotten. For I shall reveal to you the answer to

those three questions about how these beings should live, and so on."

"Thus shall it be," replied

the junior monk Subhuti, and he sat to listen as instructed by the Conqueror. The

Conqueror too then began, with the following words: In reply then Subhuti proffers to the Conqueror, "Thus

shall it be." He sits to listen as instructed by the Conqueror, and the Conqueror too

begins his explanation with the words that follow. This Subhuti, by the way, is only posing as a disciple: in reality he

would appear to be an emanation of Manjushri himself. When the Teacher spoke the sutras on

the Mother of the Buddhas, it was none other than Subhuti that he would appoint to give

the opening presentations and there is a special significance to why he did so. As for the general structure of the text, Master Kamalashila makes his

presentation in a total of eighteen different points. These begin with relating the text

to the Wish for enlightenment, and then to the perfections, and then discussing the

aspiration for the Buddha's physical body. After covering all the others, he reaches

finally the part where the Buddha has completed his pronouncement. Master Kamalashila provides his commentary by relating the first

sixteen of these points to the levels of those who act in belief. The one point that

follows then he relates to the levels of those who act out of total personal

responsibility. Point number eighteen refers, lastly, to the level of a Buddha. My intention here is to offer a somewhat more concise explanation, and

I begin with the part that concerns the Wish for enlightenment.

The following selections are taken from The Diamond Cutter Sutra, spoken

by Lord Buddha (500 BC), and the commentary to it named Sunlight on the Path to

Freedom, by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of Sera Mey Tibetan Monastery. The

root text is in bold and has been inserted into the commentary. Subhuti, this is how those who have entered well into the way of the

bodhisattva must think to themselves as they feel the Wish to achieve enlightenment: I will bring to nirvana the total amount of living beings, every single

one numbered among the ranks of living kind: those who were born from eggs, those who were

born from a womb, those who were born through warmth and moisture, those who were born

miraculously, those who have a physical form, those with none, those with conceptions,

those with none, and those with neither conceptions nor no conceptions. However many

living beings there are, in whatever realms there may be anyone at all labelled with the name of "living being" all these will I bring to total

nirvana, to the sphere beyond all grief, where none of the parts of the person are left at

all. Yet even if I do manage to bring this limitless number of living beings to total

nirvana, there will be no living being at all who was brought to total nirvana. What the root text is saying is: "Subhuti,

this is how those who have entered the way of the bodhisattva must think to themselves

first as they feel the Wish to achieve enlightenment: Whatever realms there may be, and however many living beings there are,

they reach to infinity, they are countless. If one were to classify those numbered

among the ranks of living kind by type of birth, there would be four: those who

were born from eggs, and then those who were born from a womb, those who were born

through warmth and moisture, and those who were born miraculously. Then again there are the sentient beings living in the desire realm

and the form realm: those who have a physical form. There are also the beings in

the formless realm: those with no physical form. There are "those with conceptions," meaning the beings

who live in all the levels except the ones known as the "great result" and the

"peak of existence." There are "those with no conceptions,"

which refers to a portion of the beings who reside at the level of the great result. In

addition are the beings who have been born at the level of the peak of existence: those

with no coarse kinds of conceptions but who on the other hand are not

such that they have no subtle conceptions. The point, in short, is that I speak of all living beings:

of anyone at all labelled with the name of "living being." All these will I

bring to total nirvana, to the sphere beyond all grief, where one no longer remains in

either of the extremes and where none of the two kinds of obstacles, and none of

the suffering heaps of parts to the person, are left at all. To summarize, these bodhisattvas develop the Wish for the sake of

bringing all these different living beings to the state of that nirvana where one no

longer remains in either of the extremes; to bring them to the dharma body, the essence

body, of the Buddha. The reference here is either to someone who is feeling the Wish for

the first time, or to someone who has already been able to develop it. The first of these

two has been practicing the emotion of great compassion, where one wishes to protect all

living beings from any of the three different kinds of suffering they may be experiencing.

This has made him ready for his first experience of the state of mind where he intends to

lead all sentient kind to the ultimate nirvana. The latter of the two, the one who has

already developed the Wish, is re-focussing his mind on his mission, and thus increasing

the intensity of his Wish. Here is a little on the four types of birth. Birth from an egg exists

among humans, serpentines, birds, and other creatures. Birth from the womb is found with

humans and animals, and is also one of the ways in which craving spirits take birth. There

are many examples of inanimate objects which grow from warmth and moisture crops and so

on. Among humans though there was the case of the king called "Headborn." The

majority of the insects which appear in the summer are also born this way. Miraculous

birth occurs with the humans who appear at the beginning of the world, and with pleasure

beings, hell beings, inbetween beings, and near pleasure-beings. It is also one of the

ways in which animals take birth. An example of birth from an egg among humans would be

the story that we see of Saga, who possessed the lifetime vows of a laywoman. She gave a

great number of eggs, and from these eggs grew boys. The above description applies to the way in which a person thinks as he

or she feels what we call the "deceptive" Wish for enlightenment. It refers both

to the Wish in the form of a prayer and to the Wish in the form of actual activities. I

would say as well that Lord Buddha's intention at this point is to refer primarily to the

Wish as it occurs at the paths of accumulation and of preparation. For a person to feel a Wish for enlightenment which is complete in

every necessary characteristic, it is not sufficient simply to intend to lead all other

sentient beings to the state of Buddhahood. Rather, you must have the desire that you

yourself reach this state as well. This is exactly why Maitreya stated that "The Wish

for enlightenment consists of the intention to reach total enlightenment for the sake of

others." The part about "the sake of others" is meant to indicate that you

must intend to lead other beings to nirvana, whereas the part about the "intention to

reach total enlightenment" means that you must intend to reach perfect Buddhahood

yourself. Lord Buddha wants us to understand that this Wish for enlightenment

must be imbued with that correct view wherein you perceive that nothing has a self-nature.

This is why He states that we must develop a Wish for enlightenment where we intend to

lead this limitless number of living beings to the nirvana beyond both

extremes, but where at the same time we realize that, even if we do manage to bring

them to this total nirvana, there will be no living being at all who achieved it, and

who also existed ultimately. The Tibetan term for "nirvana" means "passing beyond

sorrow." The "sorrow" mentioned here refers to the pair of karma and mental

afflictions, as well as to suffering. The nirvana to which you wish to bring beings then

refers to a state of escaping from the combination of karma and bad thoughts, along with

suffering: it means to go beyond them. This is why the unusual Tibetan verb here refers

not only to nirvana, but to the act of bringing someone to nirvana as well. The

root text at this point is meant to indicate that ordinary beings can possess something

that approximates the ultimate Wish for enlightenment. It is also indicating the existence

of the actual ultimate Wish for enlightenment, which only realized beings possess. At this juncture in his commentary, Master Kamalashila presents a great

deal of explanation concerning the correct view of reality. He does so because he realizes

that this background is very important for a proper understanding of the remainder of the

root text, which is all spoken relative to the correct view of emptiness. If I did the

same here in my own commentary I fear it would become too long for the reader, and so I

will cover some of these points now, but only in the very briefest way, just to give you a

taste. Now each and every existing object, be it part of the afflicted part of

existence or part of the pure side, is established as existing only by virtue of terms. If

one performs an analysis with reasoning which examines an object in an ultimate sense, no

object can bear such examination, and we fail to locate what we gave our label. Here the

thing we deny is easier to deny if we can identify it clearly. As such I will speak a bit

about what this thing we deny is like. Generally speaking there are a great number of different positions that

exist about what the object we deny exactly is. Here though I will give my explanation

according to the position of the Consequence section of the Middle-Way school. A certain

sutra says that "They are all established through concepts." The Commentary

to the Four Hundred too contains lines such as the one which says, "It is only

due to the existence of concepts that existence itself can exist, and..." The Lord,

in his Illumination of the True Thought, says as well that "These lines [from

sutra] are describing how all existing things are established by force of concepts; and we

see many other such statements, that all existing objects are simply labelled with our

concepts, and are established only by force of concepts." There is a metaphor used to describe how all existing things are

labelled with our concepts. When you put a rope with a checkered pattern on it in a dark

corner, some people might get the impression that it's a snake. The truth at this point

though is that nothing about the rope is a snake: neither the rope as a whole, nor the

parts of the rope. Nonetheless the person thinks of the rope as a snake, and this snake is

an example of something which only makes its appearance as something labelled with a

concept. In the same way, the heaps of parts that make us up serve as a basis

for us to get the impression "This is me." There is nothing at all about these

heaps as a whole, nor their continuation over time, nor their separate components, that we

could establish as being an actual representation of "me." At the same time

though there is nothing else, nothing essentially separate from these heaps of parts to

ourselves, that we could consider an actual representation of "me" either. As

such, this "me" is merely something labelled upon the heaps of parts that make

us up; there is nothing which exists by its own essence. This too is the point being made in the String of Precious Jewels,

by the realized being Nagarjuna: If it's true that the persona is not the element Of earth, nor water, nor fire, nor wind, Not space, or consciousness, not all of them, Then how could he ever be anything else? The part of the verse that goes from "not earth" up to

"not consciousness" is meant to deny that you could ever establish a self-nature

of the person in any of the six elements that make up a persona, considered separately.

The words "not all of them" are meant to deny that you could establish such a

self-nature in the collection of the six elements, considered as a whole. The final line

of the verse denies that there could be any self-nature which was essentially separate

from these same elements. How then do we establish the existence of the persona (which in this

case simply means "person")? The same work says: Because the persona includes all six Elements, he's nothing that purely exists; Just so, because they include their parts, None of these elements purely exist. Given the reason stated above, the persona is nothing more than

something labelled upon the six elements that make him up he does not though purely exist. Just so none of these elements themselves exist purely, for they too

are simply labelled upon the parts that they include. This same reasoning can be applied

to the heaps of parts that make up a person, and all other objects as well: you can say

about all of them that, because they are labelled on their parts and their whole, they do

not exist independently. The physical heap of parts that I myself possess is something

labelled upon my five appendages and so on; these appendages themselves are something

labelled upon the body as a whole and the parts that go off to each side of it; and the

smaller appendages like fingers and toes too are labelled upon their whole and their

parts. A water pitcher is something labelled on its spout and base and other

parts; the spout and base and such in turn are labelled on their parts and whole; and so

on the same pattern applies to all physical objects. Mental things too are labelled on

mental events of successive moments, and through the objects towards which they function,

and so on. Even uncaused phenomena are labelled upon the respective bases that take their

labels. All this I have covered before, in other writings. Given the above, there does not exist anything which does not occur in

dependence, or which is not labelled through a dependent relationship. Therefore the point

at which we can say something is the object denied by our search for a hypothetical

self-existent thing would be any time that thing existed without having been labelled

through a dependent relationship. This too is why the Root Text on Wisdom states: No object which does not occur Through dependence even exists at all; As such no object could exist At all if it weren't empty. In short, when you search for the thing given the name of

"self" or "me" you will never find anything; despite this, the fact

that things can do something is completely right and proper, in the sense of an

illusion, or magic. And this fact applies to each and every existing thing there is. As

the Shorter [Sutra on the Perfection of Wisdom] states, You should understand that the nature of every single living is the

same as that of the "self." You should understand that the nature of all existing objects is the

same as that of every living being. The King of Concentration says as well, You should apply what you understand about how You think of your "self" to every thing there is. All this is true as well for objects like the perfection of giving and

so on: they exist only through being labelled with a term, and are empty of any natural

existence. Seeking to make us realize how necessary it is to understand this fact, Lord

Buddha makes statements like "Perform the act of giving without believing in any

object at all." This is the most important thing for us to learn: so long as we are

still not free of the chains of grasping to things as truly existing, and so long as we

have yet to grasp the meaning of emptiness, then we will never be able to achieve freedom,

even if the Buddha should appear himself and try to lead us there. This is supported by

the words of the savior Nagarjuna: Freedom is a complete impossibility For anyone who does not understand emptiness. Those who are blind will continue to circle Here in the prison of six different births. Master Aryadeva as well has spoken that "For those who conceive of

things, freedom does not exist." And there are many other such quotations. Why is it so? Because, Subhuti, if a bodhisattva were to conceive of

someone as a living being, then we could never call him a "bodhisattva." Here we return to where we left off in the root text. One may ask, "Why

is it so? What reason is there for saying that we should develop a Wish for

enlightenment, while still understanding that there is no truly existing sentient being at

all who ever achieves it?" Lord Buddha first calls Subhuti by name, and then

explains that we could never call any particular bodhisattva a "bodhisattva

who had realized the meaning of no-self-nature" if this bodhisattva were to

conceive of any living being as a living being who existed truly.

The following selections are taken from Sunlight on the Path to

Freedom, written by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of Sera Mey Tibetan

Monastery. The original root text of the sutra by Lord Buddha is included in darker type. Why is that? Think, oh Subhuti, of the

mountains of merit collected by any bodhisattva who performs the act of giving without

staying. This merit, oh Subhuti, is not something that you could easily ever measure. One would have to admit that a person locked in the chains of grasping

to some true existence can collect a great amount of merit through acts of giving and the

like. But suppose a person is able to practice giving and the rest after he has freed

himself from these same chains. His merit then is certain to be ever much greater. And it

is to emphasize this point that the Buddha says, Why is that? Think, oh Subhuti, of the

mountains of merit collected by any bodhisattva who performs the act of giving without

staying. This merit is not something whose limit you could easily ever measure;

in fact, it would be quite difficult to measure. Oh Subhuti, what do you think? Would it

be easy to measure the space to the east of us? And Subhuti replied, Oh Conqueror, it would not. The Conqueror bespoke: And just so, would it be easy to measure the space to the south of us,

or to the north of us, or above us, or below us, or in any of the ordinal directions from

us? Would it be easy to measure the space to any of the ten directions from where we now

stand? And Subhuti replied, Oh Conqueror, it would not. The Conqueror bespoke: And just so, oh Subhuti, it would be no easy thing to measure the

mountains of merit collected by any bodhisattva who performs the act of giving without

staying. The root text here is presenting an example. It would be no easy thing

to measure the space to the east or any of the rest of the ten directions reaching out

from the particular point where we are now. Then the Buddha summarizes the point of the

example with the words that start with "Just so, Subhuti..." Oh Subhuti, what do you think? Should we

consider someone to be the One Thus Gone because he possesses the totally exquisite marks

on a Buddha's body? And Subhuti replied, Oh Conqueror, we should not. We should not consider someone the One

Thus Gone because he possesses the totally exquisite marks on a Buddha's body. And why

not? Because when the One Thus Gone himself described the totally exquisite marks on a

Buddha's body, he stated at the same time that they were impossible. And then the Conqueror spoke to the junior monk Subhuti again, as

follows: The merit of acts such as giving and the rest bring us the physical

body of a Buddha, and this physical body is adorned with various marks and signs. The

words "Subhuti, what do you think?" mean "Subhuti, turn your mind to

this subject, and think about how it could be contemplate upon it." The Buddha then asks Subhuti, "Assume for a minute that someone

possessed the totally exquisite marks and signs, or the two physical bodies, of the

One Thus Gone. Would that in itself require us to consider him that is, assert that

he is the One Thus Gone? What do you think?" Subhuti replies to the Buddha with the words starting off from, "We

should not consider him so." At this point we have to draw a slight distinction.

One should not necessarily consider someone the One Thus Gone simply because he

possesses the totally exquisite marks and signs. "And why not?" says

Subhuti. He answers himself by saying, "Because when the One Thus Gone himself

described the totally exquisite marks and signs on a Buddha's body, he stated at the same

time that they existed deceptively, in the way of an illusion. Signs and marks of this

kind that existed ultimately, however, would be a complete impossibility." Oh Subhuti, what do you think? The totally

exquisite marks on a Buddha's body, as such, are deceptive. The totally exquisite marks on

a Buddha's body are also not deceptive, but only insofar as they do not exist. Thus you

should see the One Thus Gone as having no marks, no marks at all. Thus did the Conqueror speak. And then the junior monk Subhuti replied

to the Conqueror, as follows: The marks and signs on the physical body of the Buddha are like an

image drawn on a piece of paper: they are not the real thing they exist in a deceptive

manner, as things that occur when all of their causes have gathered together. They do not

exist as something with a true nature. To indicate this fact, Lord Buddha says to Subhuti,

"Insofar as the totally exquisite marks on a Buddha's body exist, as such

they are deceptive. "Just what," you may ask, "is meant by the word deceptive?"

The totally exquisite marks and signs on a Buddha's body are also not deceptive,

and true, but only insofar as they do not exist truly. Thus you should see the

One Thus Gone as having no marks, no marks to indicate his nature, at all. The section here helps to prevent us from falling into either one of

the two extremes. The physical body of the Buddha and its various marks and signs do exist

albeit in a deceptive way, in a false or empty way and this fact keeps us from the extreme

of denying the existence of something which actually does exist. The text though also states that there exist no marks, and no marks

that would indicate any nature, which also exist truly. This fact keeps us from the

extreme of asserting the existence of something which actually does not exist. The former

of these two [marks] is referring to the physical body of a Buddha. The latter is

referring to the dharma body, and chiefly to the essence body.

The following selections are taken from Sunlight on the Path to

Freedom, written by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of Sera Mey Tibetan

Monastery. The original root text of the sutra by Lord Buddha is included in darker type. Oh Conqueror, what will happen in the

future, in the days of the last five hundred, when the holy Dharma is approaching its

final destruction? How could anyone of those times ever see accurately the meaning of the

explanations given in sutras such as this one? And the Conqueror bespoke, Oh Subhuti, you should never ask the question you have just asked:

"What will happen in the future, in the days of the last five hundred, when the

Dharma is approaching its final destruction? How could anyone of those times ever see

accurately the meaning of the explanations given in sutras such as this one?" The issue is whether or not there will be anyone at all in

the future who believes in, or has any great interest in, sutras such as this one sutras

which explain the nature of the dharma body, and the physical body, of a Buddha. In

order to raise this issue, Subhuti asks the question that begins with "Oh

Conqueror, what will happen in the future, in the days of the last five hundred, when the

holy Dharma is approaching its final destruction?" In reply, the Conqueror speaks: "Oh Subhuti, you should never

ask the question you have just asked." What he means here is that Subhuti should

never entertain the uncertainty of wondering whether or not there will be anyone of this

type in the future; and if he never had this doubt, Subhuti would never ask the question. And again the Buddha bespoke, Oh Subhuti, in the future, in the days of the last five hundred, when

the holy Dharma is approaching its final destruction, there will come bodhisattvas who are

great beings, who possess morality, who possess the fine quality, and who possess wisdom. And these bodhisattvas who are great beings, oh Subhuti, will not be

ones who have rendered honor to a single Buddha, or who have collected stores of virtue

with a single Buddha. Instead, oh Subhuti, they will be ones who have rendered honor to

many hundreds of thousands of Buddhas, and who have collected stores of virtue with many

hundreds of thousands of Buddhas. Such are the bodhisattvas, the great beings, who then

will come. Oh Subhuti, says the text, in the future, even when the

holy Dharma is approaching its final destruction, there will come bodhisattvas who are

great beings. They will possess the extraordinary form of the training of morality;

they will possess that fine quality which consists of the extraordinary form of the

training of concentration, and they will possess the extraordinary form of the

training of wisdom. And these bodhisattvas who are great beings will not be ones who have

rendered honor to or collected stores of virtue with only a single Buddha, but instead

they will be ones who have rendered honor to and collected stores of virtue with many

hundreds of thousands of Buddhas. This fact, says the Conqueror, is something I can

perceive right now. Master Kamalashila explains the expression "days of the last

five hundred" as follows: "Five hundred" here refers to a group of five hundreds; it

refers to the well-known saying that "The teachings of the Conqueror will remain for

five times five hundred." As such, the "five times five hundred" refers to the length

of time that the teachings will remain in the world: 2,500 years. On the question of just how long the teachings will survive in this

world, we see a number of different explanations in the various sutras and commentaries

upon them. These state that the teachings of the Able One will last for a thousand years,

or two thousand, or two and a half thousand, or five thousand years. When we consider

their intent though these various statements are not in contradiction with each other. The reason for their lack of contradiction is that some of these works

are meant to refer to the length of time that people will still be achieving goals, or

still be practicing. Still others refer to the length of time that the physical records of

these teachings remain in our world. Some, finally, appear to be referring to the Land of

the Realized [India]. There are many examples of the kinds of bodhisattvas mentioned in the

text. In the Land of the Realized, there have been the "Six Jewels of the World of

Dzambu," and others like them. In Tibet there have been high beings like the Sakya

Pandita, or Buton Rinpoche, or the Three Lords the father and his spiritual sons. Oh Subhuti, suppose a person reaches

even just a single feeling of faith for the words of a sutra such as this one. The One

Thus Gone, oh Subhuti, knows any such person. The One Thus Gone, oh Subhuti, sees any such

person. Such a person, oh Subhuti, has produced, and gathered safely into himself, a

mountain of merit beyond any estimation. Suppose, says the text, that a person of those future days

learns, and then contemplates, a sutra such as his one; that is, a scripture which

teaches the perfection of wisdom. And say further that this brings him to reach, or

develop, even just a single feeling of admiration for this teaching much less any

frequent emotion of faith for it. From this moment on the One Thus Gone knows

and sees that any such person has produced, and gathered safely into himself, a mountain

of merit beyond any estimation. He "knows" the person's thoughts, and

"sees" his visual form and such. Why is it so? Because, Subhuti, these

bodhisattvas who are great beings entertain no conception of something as a self, nor do

they entertain any conception of something as a living being, nor any conception of

something as being alive, nor any conception of something as a person. One may ask the reason why the above is so. It's because these

particular bodhisattvas will entertain no manifest conception of

something as a self, or as a living being, or as being alive, or as a person. The

denotation of the words "self" and "person" and so on here are the

same as I have mentioned earlier. Master Kamalashila at this point says: The expression "conceive of something as a self" means

thinking "me," or grasping that the self exists. "Conceiving of something

as a living being" means grasping that something belonging to the self exists.

"Conceiving of something as being alive" means continuing to grasp to the same

"self" as above, but for the entire length of its life. "Conceiving of

something as a person" means grasping that those who are born again and again are

born. Thus the meaning of grasping to something as belonging to the self is a

bit different than before. When the text says that these bodhisattvas entertain no such

coarse conceptions, it is referring specifically to the occasions at which one

realizes the lack of a self-nature. Oh Subhuti, these bodhisattvas who are great beings neither entertain

any conception of things as things, nor do they entertain any conception of things as not

being things. They neither entertain any conception of a thought as a conception, nor do

they entertain any conception of a thought as not being conception. Why is it so? Because if, oh Subhuti, these bodhisattvas who are great

beings were to entertain any conception of things as things, then they would grasp these

same things as being a "self"; they would grasp them as being a living being;

they would grasp them as being something that lives; they would grasp them as a person. And even if they were to entertain them as not being things, that too

they would grasp as being a "self"; they would grasp as being a living being;

they would grasp as being something that lives; they would grasp as a person. The text is saying: "Not only do these beings avoid entertaining a

belief in things as being something true; neither do they entertain any conception of

physical form and other things as being true things nominally. Nor as

well do they entertain any conception where they believe that these things are

not things." From another point of view, it is appropriate as well to gloss the

passage as follows. Physical form and other such things are deceptive objects, and

deceptive objects are not something which is true. These bodhisattvas avoid entertaining

even the conception where one believes that this fact itself is something true. If one in

fact did entertain such a conception, then certain problems would arise and this explains

the relevance of the two paragraphs that come next in the root text, the one that mentions

"If they were to entertain any conception of things as things" and so on;

and the other that starts with "If they were to entertain them as not being

things" that had a self. With this next section of the sutra, Lord Buddha wishes to demonstrate

a certain fact. In the sections above we have spoken about the act of becoming

enlightened, and of teaching the dharma, and so on. Neither these, nor any other object in

the universe, exists ultimately. Nonetheless, they do exist nominally. As such, one would

have to admit that anyone who performs an act of giving does acquire great merit thereby.

Yet anyone who carries out the process of learning, or contemplating, or meditating upon

this teaching acquires infinitely greater merit. To convey this point, the Conqueror asks Subhuti the

question beginning with "What do you think? Suppose some son or daughter of noble

family were to take this great world system, as system with a thousand of a thousand of a

thousand planets..." The system mentioned here is described in the Treasure

House [of Higher Knowledge, the Abhidharmakosha,] as follows: A thousand sets of all four continents with A sun and moon, Mount Supreme, pleasure Beings of the desire, and world of the Pure agreed as an elementary system. A thousand of these is a second-order kind, The intermediate type of world system. A third-order system is a thousand of these. "Suppose further," continues Lord Buddha, "that they

were to fill up this system of planets with the seven kinds of precious substances:

with gold, silver, crystal, lapis, the gem essence [emerald], karketana stone, and

crimson pearl. And say then that they offered them to someone. Would they create many

great mountains of merit from such a deed, from giving someone else such a gift?" And Subhuti replied, Oh Conqueror, many would it be. Oh Conqueror, it would be many. This

son or daughter of noble family would indeed create many great mountains of merit from

such a deed. And why so? Because, oh Conqueror, these same great mountains of merit are

great mountains of merit that could never exist. And for this very reason do the Ones Thus

Gone speak of "great mountains of merit, great mountains of merit." In response, Subhuti replies: It would be many great mountains of merit and these great mountains

of merit are mountains of merit that we could establish as existing only in name, only in

the way that a dream or an illusion exists: these same great mountains of merit though

could never exist as mountains that existed ultimately. The Ones Thus Gone

as well speak in a nominal sense of "great mountains of merit, great

mountains of merit" applying the name to them. This section is meant to demonstrate a number of different points.

Black and white deeds that you have committed before now, and which you are going to

commit later, are such that the ones in the past have stopped, and the ones in the future

are yet to come. Therefore they are non-existent, but we have to agree that, generally

speaking, they exist. We also have to agree that they are connected to the mind stream of

the person who committed them, and that they produce their appropriate consequences for

this person. These and other difficult issues are raised in the words above. And the Conqueror bespoke: Oh Subhuti, suppose some son or daughter of noble family were to take

all the planets of this great world system, a system with a thousand of a thousand of a

thousand planets, and fill them all up with the seven kinds of precious substances, and

offer them to someone. Suppose on the other hand that one of them held but a single verse

of four lines from this particular dharma, and explained it to others, and taught it

correctly. By doing the latter, this person would create many more great mountains of

merit than with the former: they would be countless, and beyond all estimation. We should first say something about the word "verse"

here. Although the sutra in Tibetan is not written in verse, the idea is that one could

put it into verse in Sanskrit. The word "hold" refers to "holding in

the mind," or memorizing. It can also apply to holding a volume in one's hand and, in

either case, reciting the text out loud. The phrase "explain it correctly" is explained as

stating the words of the sutra and explaining them well. The phrase "teach it

correctly" is explained as teaching the meaning of the sutra well, and this is

the most important part. Suppose now that one held the sutra and did the other things

mentioned with it, rather than the other good deed described. This person would

then create great mountains of merit that were ever more countless, and beyond all

estimation. Why is it so? Because, Subhuti, this is

where the matchless and totally perfect enlightenment of the Ones Thus Gone, the

Destroyers of the Foe, the Totally Enlightened Buddhas, comes from. It is from this as

well that the Buddhas, the Conquerors, are born. The reason for this is as follows. The act of giving someone the dharma

is of much more benefit that the act of giving material things. Not only that, but the

enlightenment of the totally enlightened Buddhas comes from is achieved through the

perfection of wisdom: the realization of emptiness which forms the subject matter of this

text. It is from putting this into practice as well that the Buddhas, the

Conquerors, are born.

The following selections are taken from Sunlight on the Path to

Freedom, written by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of Sera Mey Tibetan

Monastery. The original root text of the sutra by Lord Buddha is marked with an ornament

in the Tibetan and bold in the English. Oh Conqueror, I declare that the Ones

Thus Gone those Destroyers of the Foe who are the Totally Enlightened Buddhas reside in

the highest of all those states that are free of the mental afflictions. I am, oh

Conqueror, a person who is free of desire; I am a foe destroyer. But I do not, oh Conqueror, think to myself, "I am a foe

destroyer." For suppose, oh Conqueror, that I did think to myself, "I have

attained this very state, the state of a foe destoyer." If I did think this way, then

the One Thus Gone could never have given me the final prediction: he could never have

said: "Oh son of noble family, oh Subhuti, you will reach the highest of all those states that are free of the mental afflictions. Because you stay

in no state at all, you have reached the state free of mental afflictions; you have

reached what we call the 'state free of mental afflictions.' Then Subhuti explains, "I am,

nominally speaking, a foe destroyer. But it is also true that I do not,

while grasping to some true existence, think to myself, "I am a foe

destroyer." If I did grasp to it this way then I would start to have mental

afflictions, and then I would stop being a foe destroyer. I am a foe destroyer, and the

Conqueror has given me the final prediction: he has told me, "Nominally

speaking Subhuti, son of noble family, you will reach the highest of all those states

that are free of the mental afflictions." In an ultimate sense though, because

I stay in no state at all, he could never have given me the final prediction, he

could never have said, "Oh son of noble family, oh Subhuti, you will reach the state

free of mental afflictions." This is because, ultimately speaking, there does not

even exist any place to stay, not thing to make one stay there, nor even anyone who stays

there. All this is consistent with the position of the Consequence school, which says that

grasping to some true existence is a mental affliction. The Conqueror bespoke: Oh Subhuti, what do you think? Was there any dharma at all which the

One Thus Gone took up from that One Thus Gone, the Destroyer of the Foe, the Perfectly

Enlightened Buddha called "Maker of Light"? And Subhuti respectfully replied, Oh Conqueror, there was not. There exists no dharma at all which the

One Thus Gone received the One Thus Gone took up from that One Thus Gone, the Destroyer of

the Foe, the Perfectly Enlightened Buddha called "Maker of Light." Ultimately speaking then there is nothing for one to achieve, and

nothing that helps one achieve it, and no one even to do the achieving. But we can say

even further that, again speaking ultimately, there is no dharma at all that one takes up,

and practices. In order to demonstrate this point, Lord Buddha states the following. The Conqueror asks, "Oh Subhuti, do you think that there was any

dharma at all which I, the One Thus Gone, in those days long ago took up,

ultimately speaking, from the Buddha called 'Maker of Light'?" And Subhuti offers up the reply, "No, there was no

such dharma." This specific reference, wherein Lord Buddha speaks of the Buddha

"Maker of Light" by name, recalls an event which had taken place long before. In

those times our Teacher was a youth known as "Cloud of Dharma." Due to the

blessing of the Buddha "Maker of Light," he was able to achieve a stage known as

the "great mastery of things that never grow," and to bring about the eighth

bodhisattva level. When this had happened, Light Maker gave him the final prediction,

saying "In the future, you will become the Buddha known as 'Shakyamuni'." In

order to remember the kindness that Light Maker paid on this occasion, I will speak more

of this later on. We should say a little about this expression, the "great mastery

of things that never grow." This refers to a point at which one has eliminated the

mental afflictions, and achieved total mastery, fluency, in meditating upon non-conceptual

wisdom, which perceives directly each and every instance of the very nature of all things,

their emptiness of any natural existence. As such, all caused objects appear to this

person exclusively in the nature of an illusion, as empty of any true existence, not only

during periods of deep meditation but during the times between these meditations as well. When one reaches the stage of the great mastery of things that never

grow, one directly perceives that no object at all has any true existence. One perceives

that what was predicted to finally happen, and the thing one is to achieve, and becoming

enlightened all of them are empty of any natural existence. As such the Buddha had no

belief that he was taking up any truly existing dharma at all from the Buddha Light Maker. It is true that, at the time that the final prediction is made, the

Buddha who is predicted does not yet exist. And it is true that, by the time he becomes a

Buddha, the person who received the prediction no longer exists. In a nominal sense though

there is a single continuum, a single person, who exists from the point of the prediction

up to the point of enlightenment. There does exist a general kind of "me," one

which extends to the whole "me" of the past and the future, where we do not

divide out the separate me's of some specific points in the past and future. It is with

reference to this general "me" that the Buddha grants his final prediction, and

says "You will become such and such a Buddha." To give an example, it is true that the particular me's of specific

past or future lives, or else the particular me's of some point early on in your life, or

later on in your life, are not the "me" you are at this present moment in time.

Nonetheless it is allowable for us to say, of things that those me's have done or are

going to do, "I did that," or "I am going to do that."

It's just the same with the final prediction. We also say things like "I am going to build a house," or

"I am going to make a hat, or some clothes, or a pair of shoes." Even though the

house and the rest have no existence at the moment that we say these things, we can speak

nonetheless of them, for we are thinking of them in the sense of something that will come

about in the future. And they will occur, if only nominally; but they will not come forth

through any nature of their own. If they could come about through some nature of their

own, then the house and so forth that we must agree exist even as we speak of building or

making them could never exist at all. This is exactly the idea expressed in the Sutra

Requested by Madrupa, where it says: Anything which arises from conditions does not arise; There is no nature of arising in such a thing. Anything dependent on conditions is explained as empty; Anyone who understands emptiness is mindful. You can also apply at this point all the reasonings presented earlier

for demonstrating how things have no true existence. At some point you will gain a really correct understanding of how,

despite the fact that results do come from causes, they do not come from these causes

through any nature of their own. At that moment you will finally grasp the way in which

Middle-Way philosophy describes how, despite the fact that things are empty of any natural

existence, they can still quite properly work and function as they do. At that point too

you will have discovered the Middle Way itself, the path where the appearance of the

normal world and emptiness itself are inseparably married together. ********************* Why is it so?

Because, oh Subhuti, there was a time when the King of Kalingka was cutting off the larger

limbs, and smaller appendages, of my body. At that moment there came into my

mind no conception of a self, nor or of a sentient being, nor of a living being, nor of a

person I had no conception at all. But neither did I not have any conception. For what reason is it so? Because long ago there was a time, oh

Subhuti, when the king of Kalingka got the evil suspicion that I had engaged in

relations with his woman. And so he was cutting off the larger limbs, and smaller

appendages of my body. (The latter refers to the fingers and toes.) At that moment I practiced patience, keeping my mind on an understanding

of the lack of true existence to each of the three elements to the act of patience. As I

focussed on the "me" which exists nominally, there came into my mind no

conception where I held any belief in some truly existing "me": and so I had

no conception of anything from a truly existing "self" up to a

truly existing "person." At that moment I had no conception at all of any such conception

that something was existing truly. At the same time though it was neither as if I

had no other, nominal conceptions at all. What Subhuti is saying here is the

following. I did have the thought that I would have to keep my patience: I did have the

thought to take the pain on willingly, and not to be upset about the harm being done to

me. And I did have the kind of conception where I reconfirmed my knowledge of how I had

perceived that no existing object has any true existence. Why is it so? Suppose, oh Subhuti, that at

that moment any conception of a self had come into my mind. Then the thought to harm

someone would have come into my mind as well. The conception of some sentient being, and the conception of some living

being, and the conception of person, would have come into my mind. And because of that,

the thought to harm someone would have come into my mind as well. Here is the reason why it is so. Suppose that at that moment any

conception of a self, where I thought of "me" as existing in an ultimate

way, had come into my mind. Or suppose any of the other conceptions mentioned had

come into my mind. Then the thought to harm someone would have come into my mind as

well; but the fact is that it did not.

The root text is found in bold in the translation, and is marked with an

ornament in the Tibetan. The commentary is by Chone Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748) of

Sera Mey Tibetan Monastery. The Conqueror bespoke: Suppose, oh Subhuti, that some bodhisattva were to say, "I am working

to bring about paradises." This would not be spoken true. Lord Buddha wishes to indicate that, in order for a person to reach the

enlightenment described above, he or she must first bring about a paradise in which to

achieve the enlightenment. Therefore the Conqueror says to Subhuti, Suppose some bodhisattva were to say or think to himself while holding